Risks of Medical Waste to Human Health

Medical waste is broadly categorised into a few categories, though several countries have their own classification systems. This article explore the direct and indirect risks of medical waste to humans.

Infectious Waste

Infectious waste may contain a great variety of pathogenic micro-organisms, which may infect the human body through skin absorption, inhalation, absorption through the mucous membranes or (rarely) by ingestion. Pathological waste is among the most dangerous category of infectious waste owing to its potential of transmitting life-threatening diseases such as acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS), viral Hepatitis, typhoid fever, meningitis and rabies, to mention but a few.

Incineration is the method most commonly used in developing countries to dispose of infectious waste, though alternative technologies, such as autoclaving, are increasingly being used.

As small-scale incinerators often operate at temperatures below 800° C, the incineration process may lead to the production of dioxins, furans and other toxic pollutants as emissions and/or in bottom/fly ash. Advanced incinerator systems with flue gas abatement are thus the better option.

Although pathological waste, including anatomical waste, is often incinerated, there are often reports of illegal disposal together with non-hazardous municipal waste or illegal dumping in many regions of the world.

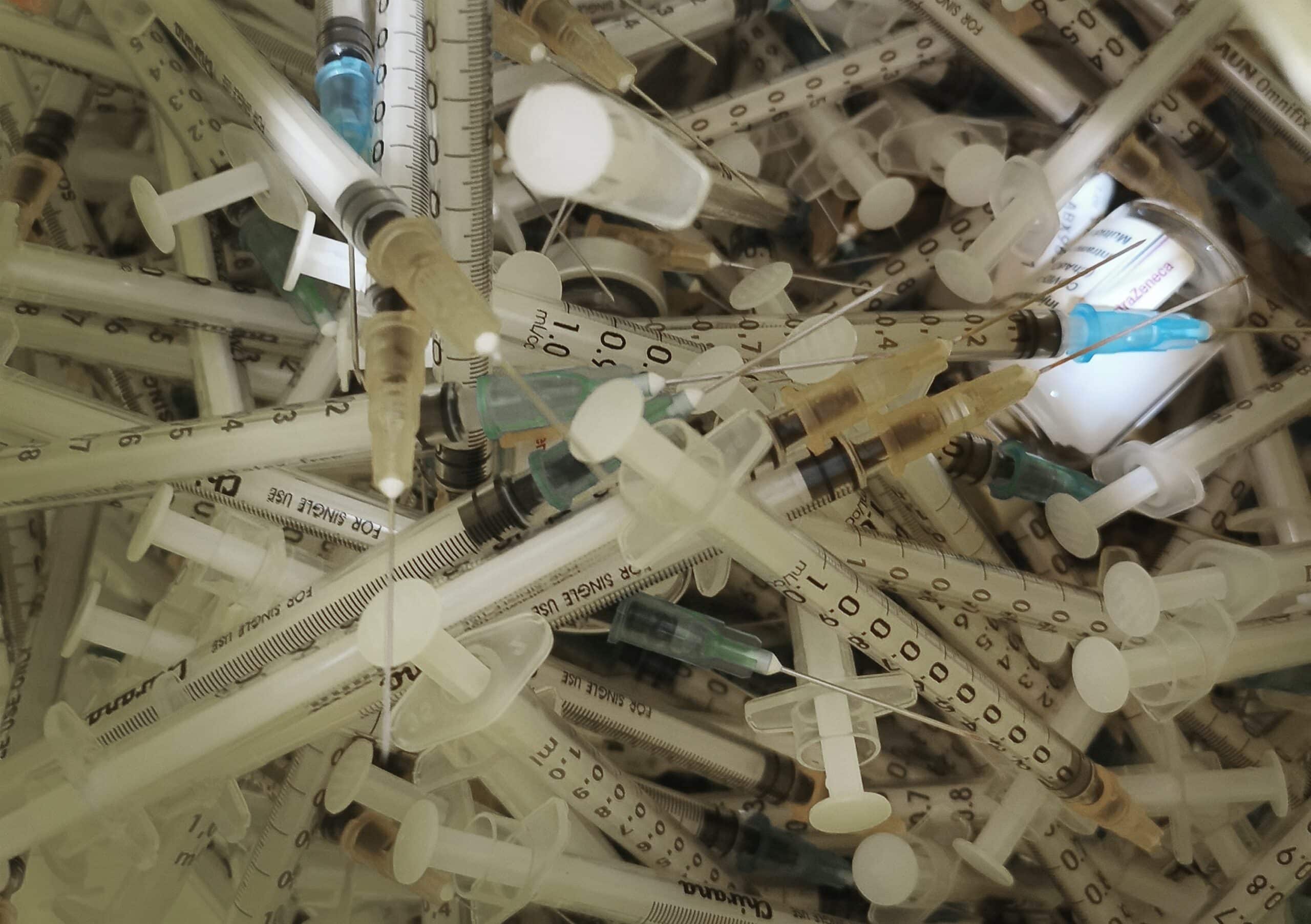

Sharps and Needles

Contaminated sharps are considered the most hazardous category of medical waste for health-care staff and the community at large. They may not only cause cuts and punctures but also infect wounds with agents previously contaminating them. Syringe needles are of particular concern because they constitute an important part of the sharps and are often contaminated with the blood of patients.

The lack of sufficient financial resources drives many health-care facilities to reuse objects and materials contaminated by blood or body fluids, such as syringes, needles and catheters. In some cases, these products are simply rinsed in a pot of tepid water between injections. In other cases, used medical products are sold to waste recyclers and then reprocessed and sold back to hospitals without proper sterilization.

The reuse of unsterilized syringes and needles exposes millions of people to infections. Worldwide, up to 40% of injections are given with syringes and needles reused without sterilization, and in some countries this proportion is as high as 70%. Other unsafe practices, such as poor collection and the dumping of dirty injection equipment in uncontrolled sites where it is easily accessible to the public, expose healthcare workers and the community to the risk of needle-stick injuries. Children are particularly at risk, since they can be hurt while playing with used needles and syringes.

Unsafe injection practices are a powerful means of transmitting blood-borne pathogens, including Hepatitis B virus, Hepatitis C virus and HIV. These viruses cause chronic infections that can lead to disease, disability and death a number of years after the injection. Epidemiological studies indicate that a person who experiences a needle-stick injury from a needle used on an infected source patient has risks of 30%, 1.8% and 0.3% of becoming infected with Hepatitis B, Hepatitis C, and HIV respectively.

In 2000, WHO estimated that injections with contaminated syringes caused 21 million cases of Hepatitis B infection (32% of all new infections), 2 million cases of Hepatitis C infection (40% of all new infections) and 260,000 cases of HIV infection (5% of all new infections).

Chemical and Pharmaceutical Waste

Many chemicals and pharmaceuticals used in health-care establishments are hazardous. Some chemicals may cause injuries, including burns. Injuries can be caused when the skin, the eyes or the mucous membrane of the lung come into contact with flammable, corrosive or reactive chemicals (such as formaldehyde or other volatile chemicals).

Other chemical and pharmaceutical products may have toxic effects through either acute or chronic exposure. Intoxication can result from absorption of the products through the skin or the mucous membranes, or from inhalation or ingestion.

Disinfectants constitute a particularly important group of hazardous chemicals, since they are used in large quantities and are often corrosive. Chemical residues discharged into the sewage system may have toxic effects on the operation of biological sewage treatment plants or on the natural ecosystems of receiving waters. Pharmaceutical residues may have the same effects, as they may include antibiotics and other drugs, heavy metals (such as mercury), phenols and derivatives and other disinfectants and antiseptics.

The severity of health hazards for health-care workers handling cytotoxic waste arises from the combined effect of the substance toxicity and the extent of exposure that may occur during waste handling or disposal. Exposure to cytotoxic substances in health care may also occur during preparation for treatment. The main pathways of exposure are inhalation of dust or aerosols, skin absorption and ingestion of food accidentally in contact with cytotoxic (antineoplastic) drugs, chemicals or waste, or from contact with the secretions of chemotherapy patients.

In most developing countries, chemical and pharmaceutical wastes are either disposed of with the rest of municipal waste or sent to cement kilns for burning. Incineration is often regarded as the safest option to dispose of obsolete pharmaceuticals in developing countries. Most small-scale medical waste incinerators are not, however, equipped with flue gas abatement technology needed to keep dioxin emissions to the levels recommended by the Stockholm Convention. A significant amount of chemicals and pharmaceuticals is also disposed of through hospital wastewater.

In countries where no wastewater treatment facilities exist, effluents from health-care facilities are discharged directly in rivers and other water streams, and risk contaminating surface and groundwater resources used for drinking and domestic purposes.

Mercury Waste

Mercury is a hazardous product common in hospitals owing to its prevalent use in a number of laboratory and medical instruments, such as thermometers and blood pressure devices, as well as in other products, such as fluorescent light tubes and batteries. It is a potent neurotoxin that can have several adverse effects on the central nervous system in adults, increase the risk of cardiovascular disease and cause kidney problems, miscarriage, respiratory failure and even death.

In the health-care context, elemental mercury may be released as a result of spillage from broken thermometers or leaking equipment. In many developing countries, there is no clean-up protocol for mercury spills. Mercury spills are not properly cleaned, and mercury waste is not segregated and managed properly. Inhalation of mercury vapours may cause damage to the lungs, kidneys and the central nervous system of doctors, nurses, other health-care workers or patients who are exposed to it.

In many developing countries, mercury waste is either incinerated with infectious waste or treated as municipal waste. If improperly disposed of, elemental mercury may travel long distances and eventually deposit on land and water, where it reacts with organic materials to form methyl mercury, a highly toxic organic mercury. This type of mercury, which affects the nerves and the brain at very low levels, bio-accumulates and become part of the aquatic food chain. The main source of human exposure to this form of mercury derives from the ingestion of contaminated fish and seafood. Even at very low levels, methyl mercury can cause severe, irreversible damage to the brain and nervous system of foetuses, infants and children.

Owing to their adverse effects on human health and the environment, mercury containing medical devices are now banned or severely restricted in many developed countries. WHO has issued technical guidance to promote the use of alternatives to mercury-containing thermometers and other medical instruments, and a global legally binding instrument to phase out the use of mercury is currently being negotiated under the auspices of the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP).

Thermometers and sphygmomanometers containing mercury continue, however, to be widely used in many developing countries. In some cases, when health-care institutions in industrialized countries decommission their old mercury-containing instruments, they donate them to institutions in developing countries. Without health-care management systems that assure the use of mercury-free devices and the proper clean-up and final disposal of mercury-containing ones, the total amount of mercury released into the environment by health-care institutions in developing countries is expected to grow in the future.

Radioactive Waste

Radioactive materials can cause harm through both external radiation (when they are approached or handled) and their intake into the body. The degree of harm depends on the amount of radioactive material present or taken into the body and on the type of material.

Exposure to radiation from high-activity sources, such as those used in radiotherapy, can cause severe injuries, ranging from superficial burns to early death. Radioactive waste arising from nuclear medicine is unlikely to cause such harm, but exposure to all levels of radiation is considered to be associated with some risk of carcinogenesis.

There are well-established procedures for minimising the hazards arising from handling radioactive materials. The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) has elaborated a number of recommendations and guidelines on the safe handling of radioactive substances produced in health-care establishments and on safe radioactive waste storage and disposal. While most hospitals and health-care facilities in developed countries comply with these safety procedures, the lack of appropriate information on the risks posed by radioactive materials and waste and on the procedures to minimize these risks may lead to their inappropriate management and disposal in some developing countries.

Dioxins and Furans

Medical waste contains a high proportion of polyvinyl chloride (PVC), a chlorinated plastic that is used in containers for blood, catheters, tubing and numerous other applications. When burned, PVC releases polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins and polychlorinated dibenzofurans (dioxins), a family of 210 persistent organic pollutants that are unintentionally formed and released from a number of industrial and incineration processes, including medical waste incineration, as a result of incomplete combustion or chemical reactions.

Dioxins are a known human carcinogen. Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia, soft-tissue sarcoma, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and Hodgkin’s disease have been linked to dioxin exposure. There is further evidence of a possible association with liver, lung, stomach and prostate cancers. Short-term high-level exposure may result in skin lesions and altered liver functions, while low-level exposure to dioxins may lead to impairment of the immune system, the nervous system, the endocrine system and reproductive functions. Foetuses and new-born children are most sensitive to exposure.

In the late 1980s, developed countries began to adopt strict regulations to reduce the amount of dioxins released into the atmosphere as a result of combustion and incineration processes. The enforcement of stricter emission standards significantly reduced the release of these substances into the environment and their concentration in many types of food (including breast milk). In the European Union, for example, industrial emissions of dioxins and furans were reduced by 80% between 1990 and 2007.

The Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants establishes that emission levels of dioxins and furans should not be higher than 0.1ng/m3. The emission standards set out in the Convention require the reduction of atmospheric emissions of dioxins and furans through the use of Incinerators with Flue Gas Abatement as well as monitoring, inspection and permitting programmes. The majority of small-scale medical waste incinerators used in developing countries do not, however, incorporate any air pollution control devices or other equipment necessary to meet modern emission standards, since this would greatly increase costs for their construction and operation.

An assessment of small-scale medical waste incinerators in developing countries showed widespread deficiencies in the design, construction, siting, operation and management of these units. These deficiencies often result in poor incinerator performance, for example, low temperatures, incomplete waste destruction, inappropriate ash disposal and dioxin emissions, which can be even 40,000 times higher than the emission limits established by the Stockholm Convention.

Poorly designed and operated incinerators used in developing countries also release significant amounts of other hazardous pollutants through gaseous emissions, fly and bottom ash, and occasionally through wastewater. Such pollutants include heavy metals (such as arsenic, cadmium, mercury and lead), acid gases, carbon monoxide and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs).